Canada & Climate Financing for Emerging Markets

I have recently taken up an interest in infrastructure investment in emerging markets. As I read on the subject, I was surprised by the scale of financing required to meet climate goals.

In Canada, the idea of the climate transition and reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is a massive deal. You see it in political campaigns, corporate reports, and even taught in schools. Not only is it mainstream, but the GHG goals set seem achievable and realistic. However, this is not the case in many countries across the world where building a ‘greener’ society is just as important in the long-term but clouded with various other short-term issues. This is often the case in emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs), which describe a subset of countries classified by a common set of economic factors.

Investopedia describes EMDCs as “transitioning from a low income, less developed, often pre-industrial economy towards a modern, industrial economy with a higher standard of living.”. EMDCs often can demonstrate partial characteristics of advanced economies, as defined by Investopedia:

High gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, which tallies up all the goods and services produced in a country in one year and divides this number by its population.

Export diversification: Countries with high GDP are not considered advanced economies if their exports consist mostly of a few commodities.

Integration into the global financial system: This includes both a country's volume of international trade and its adoption of and participation in international financial institutions.

Now that we understand exactly what EMDCs are let's look at their emissions potential.

Understanding the Emissions Potential of EMDCs

I’m going to do a mini-economics starter, as it really helped me understand how industrialization and the development of economies can impact the environment.

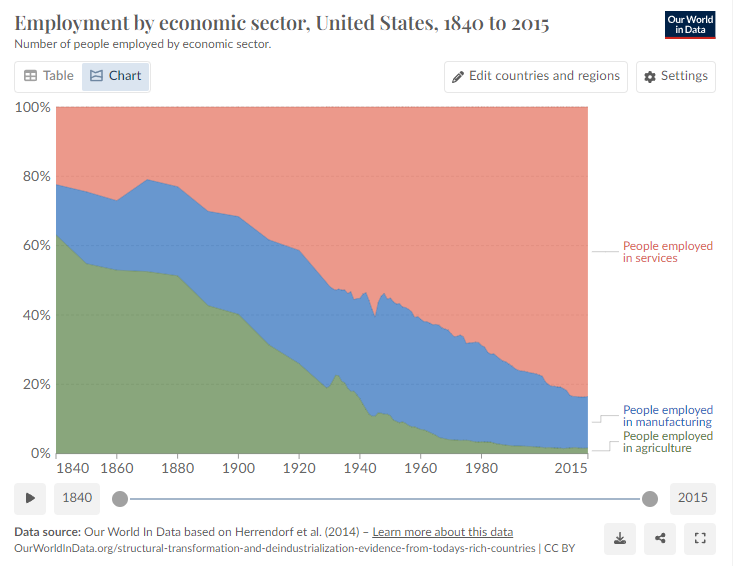

Let's start by looking at historical examples of how economic sectors shift as a country develops. Looking at the makeup of labourers in the US over time, it's clear that the economy shifted from agriculturally based to a midpoint of manufacturing dominance and then to services. This is a general trend most economies follow as they develop, relying on higher productivity economic inputs through industrialization. Looking at the graph below, it's clear the workforce has moved from being largely agrarian to service-based, a low-productivity economic sector, to a high-productivity economic sector. This is how industrialization changes the economic makeup of countries.

Similar trends, but with different time frames, are observed in many of today’s rich countries and are expected to occur with current EMDCs. Understanding this, we can start to unravel the hypothesis proposed by Kuznet: the environmental Kuznet curve. Expanding on his curve relating inequality and income per capita, the environmental curve describes a hypothesized relationship between environmental degradation and income per capita. When economies undergo industrialization and development, with a higher percentage of the population moving to the middle class or an increase in wealth, environmental degradation often increases. However, as populations become even richer, similar to what we see in advanced economies, environmental degradation decreases. EMDCs are moving towards what is seen on the graph as an industrial economy with growing middle-income levels.

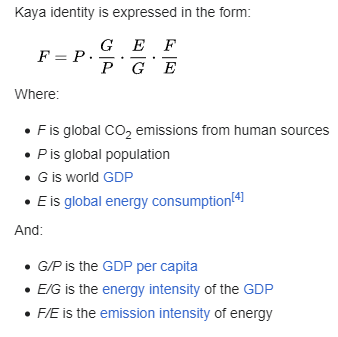

The emissions trends of emerging economies are also described through a concept called the Kaya identity, “a mathematical equation stating that the total emission level of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide can be expressed as the product of four factors: human population, GDP per capita, energy intensity (per unit of GDP), and carbon intensity (emissions per unit of energy consumed)”.

This basic economic analysis describes that the trends experienced in EMDCs, such as movement toward an industrial economy, a growing middle class, and an increasing human population, are all correlated with an increase in emissions. EMDCs are poised to be large proponents of emissions in the coming years.

According to the World Emissions Clock’s 2022 projections, EMDC countries were expected to account for 75% of global GHG emissions. This follows growing trends where EMDCs accounted for over 95% of GHG emissions increases from 2012 to 2022, up from 44% of total global emissions in 1990. Additionally, 98% of global population growth and 90% of new middle-households in this decade will be from EMDCs. With rapid industrialization in EMDCs comes the need to focus on sustainable development that advanced economies are still undergoing.

It’s no small investment and definitely not one EMDCs are equipped to handle themselves considering the current GHG emission goals set by the UN.

Quantifying the Need for Climate Financing

The IMF estimates that “financing needed to meet [climate] adaption and mitigation goals are trillions of USD annually.”. As of now, EMDCs are only seeing a mere fraction of this amount. The Tony Blair Institute (TBI) recently published insights into exactly how big this deficit is. They projected that there needs to be a 30% annual increase in EMDC-targeted climate-related financing by 2030 to meet global targets, which is seemingly less feasible considering that there has been a consistent 10% average annual decrease in EMDC climate-responsive projects since 2015. Considering these projections, EMDCs should ideally be getting $2.4T USD in annual funding, equivalent to 30-50% of their 2030 projects, with $780B from international sources, whether they be private or public in origin.

A report from the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance published through LSE expects spending needs to be much higher, stating “$1 trillion per year in external finance that [is] needed by 2030” for EMDCs other than China to achieve climate-related goals. It's clear we have a long way to go, and these hefty goals will not be achieved without the whole might of developed countries working together. Many advanced economies have looked to support EMDCs in achieving these financing goals, including Canada.

Canada’s Role in Climate Financing for EMDCs

Canada is, in fact, a global leader when it comes to working to bring climate financing to emerging markets. In 2021, at the G7 Leaders’ Summit, Canada announced intentions to double its international climate finance efforts to $5.3B CAD towards 2026. This new funding is to be implemented across a range of initiatives in 5 major categories, each with successful case studies. (A full list of current commitments can be found here)

Increasing Climate Resilience

In the last 5 year commitment (2015-2021), Canada contributed $37.5M CAD to the Least Developed Countries Fund aimed at developing national climate information infrastructure. In Malawi, this allowed weather stations to deliver advanced information to farm owners to take care of their crops better. Overall, this initiative was estimated to positively impact 5M people.

Clean Energy Transition

Canada contributed $200M CAD to the Asian Development Bank to support the development of clean infrastructure. $15M USD of this contribution went to developing a 47.5MWp floating solar plant in Vietnam, which was the first large-scale plant of its kind. Overall, this project was a huge success for clean energy development in the region.

Support for Gender Equality and Inclusive Climate Action

Canada provided over $5.3M CAD to a program in Honduras to safeguard forests under the leadership of women and rural and indigenous youths. This project helped enhance forest governance, with equal participation of women and youth, while also increasing access to education programs and business resources.

Better Access to Climate Finance

Canada helped begin the Climate Finance Access Network (CFAN) through the support of the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) and eventually provided CFAN with $9.5M CAD in funding, which primarily helped deploy the programs in climate-vulnerable countries.

Mobilizing Private Sector Investment for Climate Action.

The Canadian Climate Fund for the Private Sector in the Americas (Phase II) received a $223.5M contribution from the government, which was distributed to various initiatives. $12.5M USD went to support Nicaragua’s sugar industry transition to support the integration of a sustainable irrigation system.

It may seem like a lot at first glance, but a truly global issue like climate change requires a global effort.

Are Advanced Economies Providing Adequate Support?

Canada has been a huge advocate for climate financing for emerging markets, spearheading the push to reach the $100B USD a year goal with Germany. This original figure was developed in 2015, with the intent to reach $100B USD a year by 2020 through to 2025. In 2021, developed countries were around $10B USD short of the $100B USD goal. However, preliminary and unverified data show that the goal was met as of 2022. A two-year delay in achieving this goal may seem negligible, except when considering the next milestone is $1T USD a year starting in 2025. This is likely to prove a challenge, and developed countries must step up their game if we hope to adequately support the climate transition in emerging markets to meet the set global emissions goals. Within the broad range of the types of climate financing, there are two areas that are underperforming: adaptation finance and the mobilization of private finance. OECD reports see adaptation finance as “the key to building resilience,” from building climate-resilient infrastructure to developing local disaster response strategies. Private sector mobilization is more of an untapped cash reservoir, but one which requires work to encourage proactive involvement to de-risk potential projects, provide support and incentives, and help set up the ideal conditions for private investment in desired projects. I hope to write further about this in a future essay.

As it stands, the world is falling behind the goals set by the IMF. Despite this, even if funds are collected, there is still a question of being able to invest it effectively.

EMDCs Need More Than Money

EMDCs, more often than not, have a weak institutional system and inefficient integration into the global financial system. This can undermine the investment potential of EMDCs and the ability to deploy financing within EMDCs. There are five main risks that EMDCs usually carry when looking to deploy any type of financing.

Political & Economic Instability: EMDCs may not always have an effective political system and be free of conflict. Corruption, political volatility, and unpredictable policies are all factors that can threaten the ability to deploy climate financing.

Currency Risk: The unpredictable environment of EMDCs often affects the financial stability of the country, and part of this is the value of foreign currencies. When it comes to equity investments, this currency risk can greatly jeopardize investments.

Liquidity Risk: As seen in the characteristics of EMDCs, the lack of integration into global financial systems can slow down the ability to enter or exit financial positions in markets and securities.

Regulatory Risk: With weak institutions and unstable or underdeveloped governments, the regulatory systems of EMDCs can be very risky when creating businesses or carrying out investments.

Economic Risk: Central banks in EMDCs may not perform effectively or even exist, which affects the ability to manage interest rates and inflation. Foreign macroeconomic trends may also disproportionately affect these EMDCs due to their weak institutions.

Not all EMDCs will demonstrate a huge risk factor within each of these five areas, but the risk still exists, hence the highlighted struggle in engaging the private sector. No matter the circumstances, it does not change the fact that climate financing is very much needed. When looking at some truly effective climate financing programs, they are organizations that not only look to raise funds, but enable the effective investment and implementation of this financing.

CFAN is a great example of this.

Climate Finance Access Network (CFAN): Deep Dive

CFAN primarily focuses on climate financing for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs), which are often more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. LDCs particularly face trouble when accessing climate financing due to their weak institutional environment. CFAN is able to overcome these barriers by placing individuals highly trained in project management and financial structuring within institutions of the host countries. In addition, CFAN looks to hire locals to become actively involved in their initiatives and connect them to both donor institutions and other global advisors. I chose to highlight CFAN as they are not only a Canadian-supported initiative, but their program also focuses on improving the institutional environment of their target countries and training locals to be able to carry out project management, financing, and networking on their own. This is the other half of the issue that needs to be solved.

As seen in the Rocky Mountain Institute press release, “With initial support from Canada, CFAN launched in the Pacific in 2021 where seven advisors have since unlocked US $64.4 million in climate financing for resilience, while an additional US $463.8 million investment pipeline is under development.”. With the success of the program, at COP28 CFAN announced the launch of its Caribbean chapter with initial support from Canada and the US in addition to a partnership with the Caribbean Community Climate Change Centre (CCCCC), which is supported by various government heads of Caribbean countries.

Conclusion

Canada is doing amazing work to bring financing through various programs to EMDCs, but the fact of the matter is it’s still not enough. Although Canada does have the 9th highest GDP in the world, the realization of climate financing for EMDCs requires a global effort at an unprecedented scale. Canada may have doubled their financing this year, but it is still a mere dent in the goals set by the IMF. Additionally, these financing goals must be supported by programs to improve the institutions of target EMDCs and work to effectively implement the financing. There is clearly still a long way to go in supporting EMDCs with sustainable development and climate financing.

I hope to continue writing on climate investing in EMDCs. This includes topics from the currency risks private investors face and mitigating this risk, identifying industries and countries for growth, and more! All in time.

Thanks for reading this piece! Next week I’ll be posting my monthly newsletter.